:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Ceausescu_Hat.png)

Bucharest’s Art Safari (May 11-17) brings to the public the art collection of former Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, which includes the works of many Romanian masters. But how can the viewer mitigate Ceausescu’s image as an art lover and collector with that of a poster boy for censorship in arts? Luckily, they don’t have to, as they surprisingly overlap, and should instead delve into the complexity of the topic by exploring all its facets.

In his sumptuous residence in Bucharest’s Primaverii neighbourhood, Romania’s former dictator Nicolae Ceausescu had a private art collection that includes Romanian masters Nicolae Tonitza, Octav Bancila and Iosif Iser.

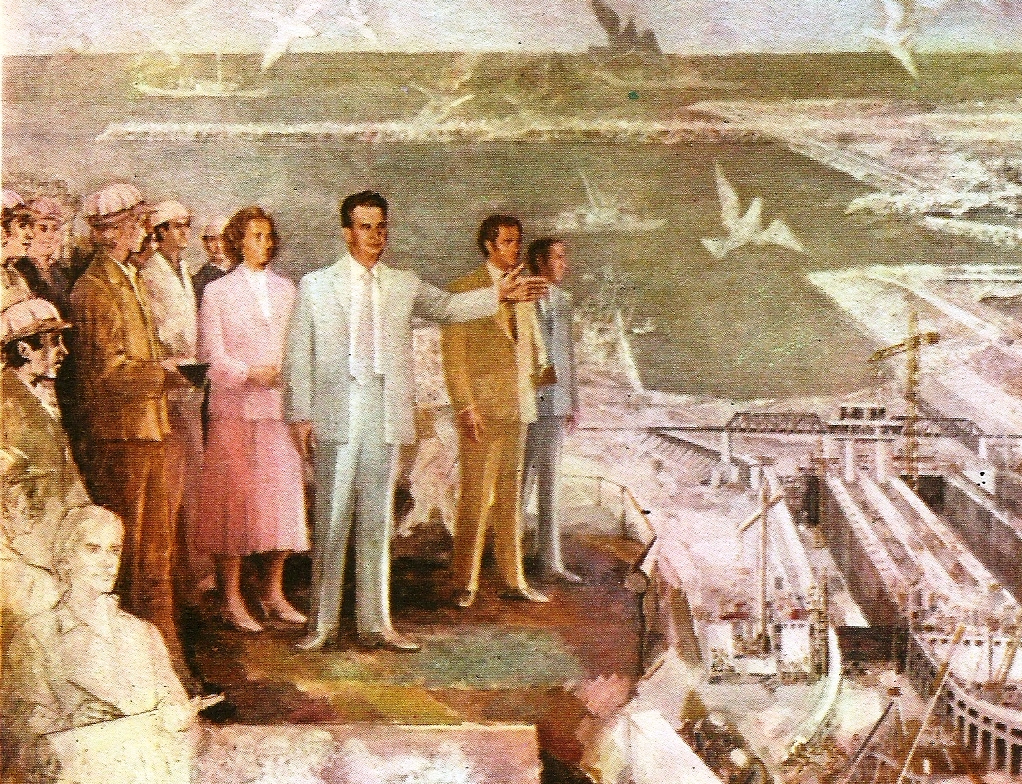

Outside those doors, however, art was subject to and forced to conform to the narrow and strict guidelines of the communist party’s policy – the “socialist realism”. Art was supposed to highlight the joy brought upon everyone by the Communist regime. All sun and no clouds or storm. When that didn’t happen, censorship was enforced, pushing art in the underground.

That is why seeing Ceausescu in the position of an art collector may seem incongruous to some. What Horia Roman Patapievici, president of the Artmark Group – one of the organisers, argues is that, by becoming a part of the discourse of the curator, his legacy is integrated into the context without being altered or reinterpreted. Instead, it the juxtaposition becomes simply ironic.

“Ceausescu is present in this combination because his traces cannot be deleted. And this is not a way to diminish the evil he represents but to mock it and say ‘You are an actor in this installation you tried to tame when you were alive. You are now part of the discourse of a curator and of an artist’,” Patapievici says, recalling instances when the regime went as far as to ask artists to shave and cut their hair to erase any trace of subjectivity.

Was he, or wasn’t he?

Ceausescu’s art collection, which he did not own but lent from Romania’s prominent museums, includes an impressive selection of paintings by artists credited with founding new schools and inspiring new artistic visions.

Hosted by the Primaverii residence, it was first seen by the public in 2016, when the palace opened for visitors. The art fair will exhibit 50 of the most outstanding pieces.

Still, in the view of Ioana Ciocan, director of Art Safari 2018, this doesn’t make the former Romanian dictator a genuine art collector.

“Ceausescu cannot be characterised as an art collector. We can say many things about him, but the fact that he was an art collector is not one. The exhibition is about yet another thing that happened in his life. But this is the first time he is regarded as someone who got to look at paintings by the masters of Romanian art.”

Conditional love

As for his relationship with art, Ciocan believes that Ceausescu knew exactly what to do with art and loved art in as much as it was a valuable medium to convey party propaganda.

“Let’s not forget that Ceausescu used contemporary art to set in motion his propaganda machine, what he wanted people to see,” she cautions.

“The art the regime was promoting, the propaganda, described a bright universe we would all one day live in. The works were utopian, highly idealised, and feature perfect young children with red cheeks releasing white doves. Then, yet another way to channel this propaganda was through the glorification of the past. Implying that we Romanians had won all the battles, withstood all challenges from outsiders and the whole of Europe was built due to us.”

“Ceausescu’s communist regime used art just like the North Korean one is using it right now, via large scale sculptures, for instance. That is why I believe Ceausescu knew what to do with art and to tell pieces of truth from Romanian history by means of it.”

Hence, it is imperative that Ceausescu’s implied love for art be scrutinised. Following Ciocan’s lead, he did love the art that depicted topics that overlapped with his vision. And in the case of the great Romanian masters he must have admired in his Primaverii residence, that was simply incidental.

“He had a preference for the works of propaganda artists, which were exhibited in all museums in Romania, and exported to other countries in the communist bloc. On the other hand, we had the traditional painters that showed an ideal – a woman who sits quietly and does embroidery, for instance. We see a warm, bright sun, the green leaves and the flowers. We are in an area that is devoid of drama, things that overwhelm you. And those who dared to do that were excluded when censorship was enforced,” she explains.

“This pushed art underground and those who took part in it had to face the consequences.”

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/1_Transport.jpg)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/IMG_6951.jpg)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/COVER-1.jpg)

:quality(80)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/cover-april.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/0x0-Supercharger_18-scaled.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Schneider-Electric-anunta-castigatorii-Sustainability-Impact-Awards-2023-in-Romania-scaled.jpg)

:quality(50)/business-review.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Premier-Energy-Group-1.jpg)